AI Context Engineering

AI Context Engineering - AI is Here to Augment Developers, Not Replace Them

Since OpenAI released ChatGPT, the technology landscape has been flooded with new AI products. Software engineers are key customers for most companies developing Large Language Models (LLMs), so the idea that AI will eliminate software engineers is not pragmatic when we look at the reality of the industry and the coding tools we now have.

Writing code has changed forever; we are in a distinct before-and-after AI stage. We now have tools to perform better and do more in less time. AI for software engineering has become as crucial as mastering your company’s main tech stack. Let me guide you through the steps to become an Agentic Coder.

Agentic Coding

An agent is more than just an automated workflow; it’s an AI-powered entity that can perform tasks autonomously, make decisions, and interact with its environment. Agents can range from simple to complex, depending on their capabilities and the tasks they are designed to perform. In software development, agents can assist developers by automating repetitive tasks, generating code snippets, even debugging code and more.

Agentic coding is like orchestrating a team of developers. You provide a detailed specification of what you want to build, and the agents take care of the rest. They have agency on how to perform the tasks, can ask you questions if they need more information, and can even learn from their mistakes. You evolve into an orchestrator of agents—defining the tasks and letting them do the work.

Context Engineering

To become an augmented engineer, you must master the art of Context Engineering. You need to know how to communicate effectively with your agents, how to break down tasks into smaller chunks, and how to evaluate the output of your agents.

My tool of choice is Claude Code. I’ve been using it for a while and have come to know its capabilities and limitations. Let’s dive into the context engineering part.

Understanding Context

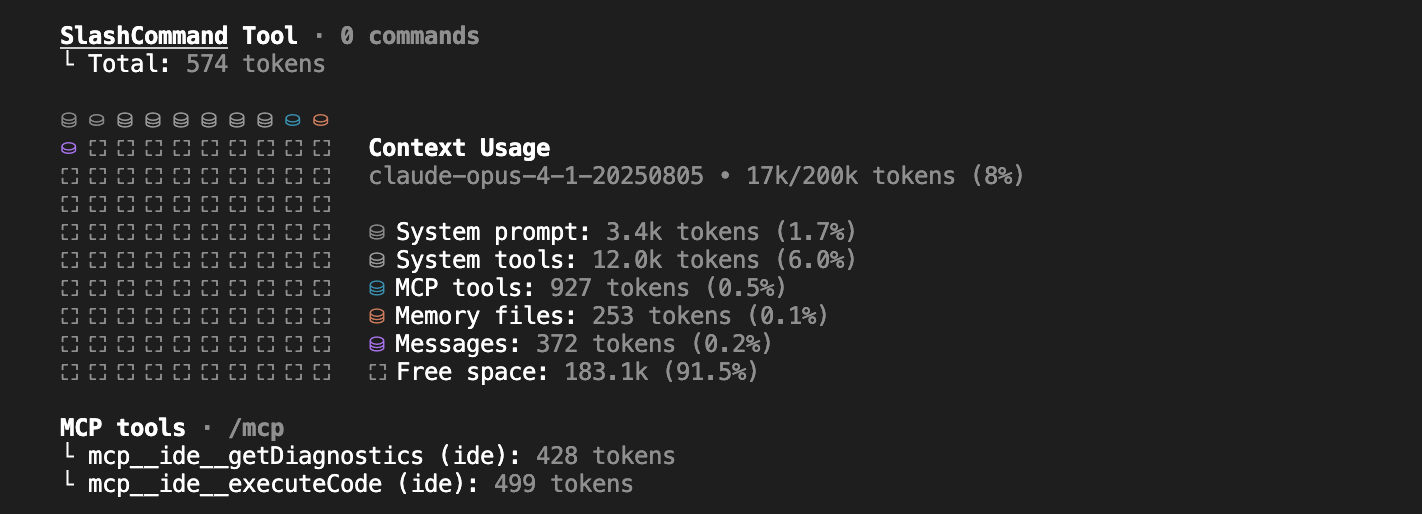

Every time we start a session in Claude, the root claude.md file is loaded into the context. If you run /context, you will see something like this:

Memory files include your claude.md files plus any other file you load into the context. Messages are the chat history; if you’ve been working on a feature for a while, the agent will have all the context of what has been discussed and what has been done.

Context engineering is knowing what to include, what to leave out, and the strategies for optimizing it. A context file can contain three types of information:

- Knowledge - facts, memories, etc.

- Instructions - prompts, memories, few-shot examples, tool descriptions, etc.

- Tools - feedback from tool calls.

Selecting the right context is crucial. Strategies for managing context are important because the better your context is, the better the results will be. However, a context that is too large can lead to worse results, so you need to find a balance. Here are some strategies that I use:

Setup Claude with Context Files

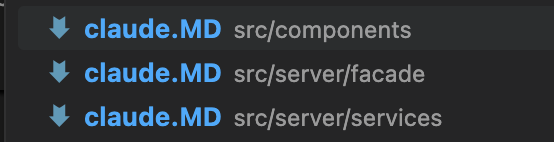

Run /init to ask Claude to generate a claude.md file for your project. Additionally, you can have claude.md files in subdirectories for specific modules, libraries, components, services, or repositories. This allows you to load only the context files needed for the tasks Claude is performing without obscuring the main context file. For example, if Claude is reading or writing files in a services directory, it will load the claude.md file in that directory.

Lazy Load Context

Lazy load context files using conditionals to avoid loading unnecessary context that consumes tokens. For example, you can have a file containing TypeScript guidelines, API documentation, or deployment instructions and ask Claude to read them only if the task is related to those topics.

Example:

//claude.md

If the task is related to typescript, read typescript_guidelines.md

If the task is related to API, read api_documentation.md

Create a File System for Agents

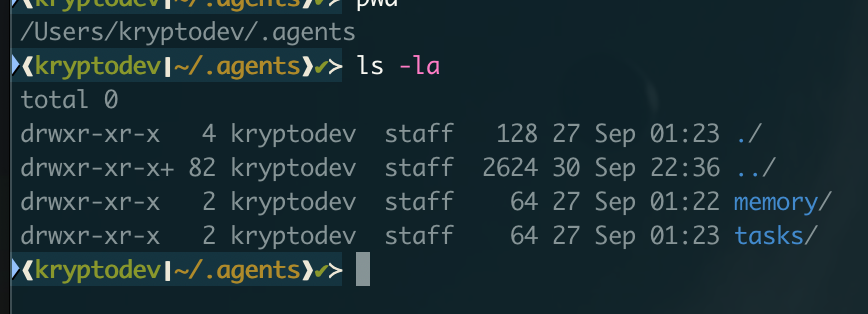

Create a file system for your main agent and sub-agents to have memory files for each task performed. This is similar to how humans work: when we do something, we remember the process and what we learned, which helps us avoid repeating mistakes and improve performance.

Examples:

// When the agent is invoked, get the insights from the memory files and add them to the context

cat ~/.agents/main/memory/2025-*/summary.json | jq '.insights[]' >> learning.md

// Get pending tasks

find ~/.agents/main/tasks -name "*.pending" -mtime -7 | wc - l

With this approach, when you clear the context using /clear, you can continue working on the same or new tasks without losing important insights from previous sessions, as your agent has the context in the file system. It’s crucial to clean the context when you are done with a task or when the conversation has become extensive (especially if Claude has read many files). This prevents context pollution and keeps the context relevant to the task at hand.

Use Plan mode and iterate until you get the desired plan. When the plan is ready, ask Claude to write it down as a markdown file with insights, references, code snippets, etc. Once the plan is finalized, clear the context, start a new fresh context, load the plan file, and ask Claude to execute it. This method yields better results because the working context is not polluted with previous conversations.

How to Use Sub Agents

In my experience, the best way to use sub-agents is to enforce separation of concerns to avoid context pollution. This doesn’t mean having a sub-agent for frontend, backend, or DevOps. Instead, focus on tasks that cause your context to be polluted, such as loading a bunch of documentation files just to learn how to use a specific library. We want to keep the main context clean and relevant.

Examples of Sub Agents:

- Documentation Agent: Responsible for reading and understanding documentation files. The main agent can invoke this sub-agent to ask questions about a library’s documentation and get answers.

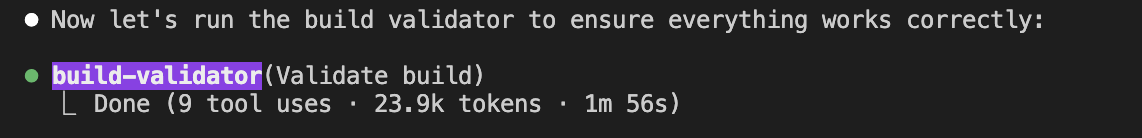

- Build Validator: Responsible for fixing a broken build. The main agent can invoke it when a task involving code changes is complete.

- Research Agent: Responsible for researching topics. It can be invoked when the main agent needs more information, allowing it to search the web, read articles, and summarize information.

In the example above, the build-validator agent runs with a fresh context to fix build errors, making it more effective than if the main agent tried to fix the errors with a polluted context. While it might sound reasonable for the main agent to fix the errors, having a sub-agent address the problem with a fresh perspective often leads to a cleaner solution because it’s not burdened by the prior conversation context.

Conclusion

In conclusion, AI is definitely here to augment developers, and understanding how to work with agents is crucial to achieve a 10x boost in productivity. The possibilities are vast, covering everything from writing unit tests and catching bad patterns to refactoring code and generating documentation. The more we experiment with agents, the more we will discover new ways to leverage them. I haven’t covered hooks here, but they are very useful too—for example, a hook to update documentation when code changes. My favorite hook is playing a sound when the agent is done with a task, so I know when to check the results.

I don’t want to forget about commands. They are very useful for automating repetitive tasks. For example, opening pull requests, code reviews, generate Pull Request descriptions, address PR comments, etc. You can create custom commands to fit your workflow.